Select a country

Vyberte krajinu

INTERNATIONAL

(EUR)

SLOVENSKO A ČESKO

(EUR)

MAGYARORSZÁG

(HUF)

POLSKA

(PLN)

Select a country

Vyberte krajinu

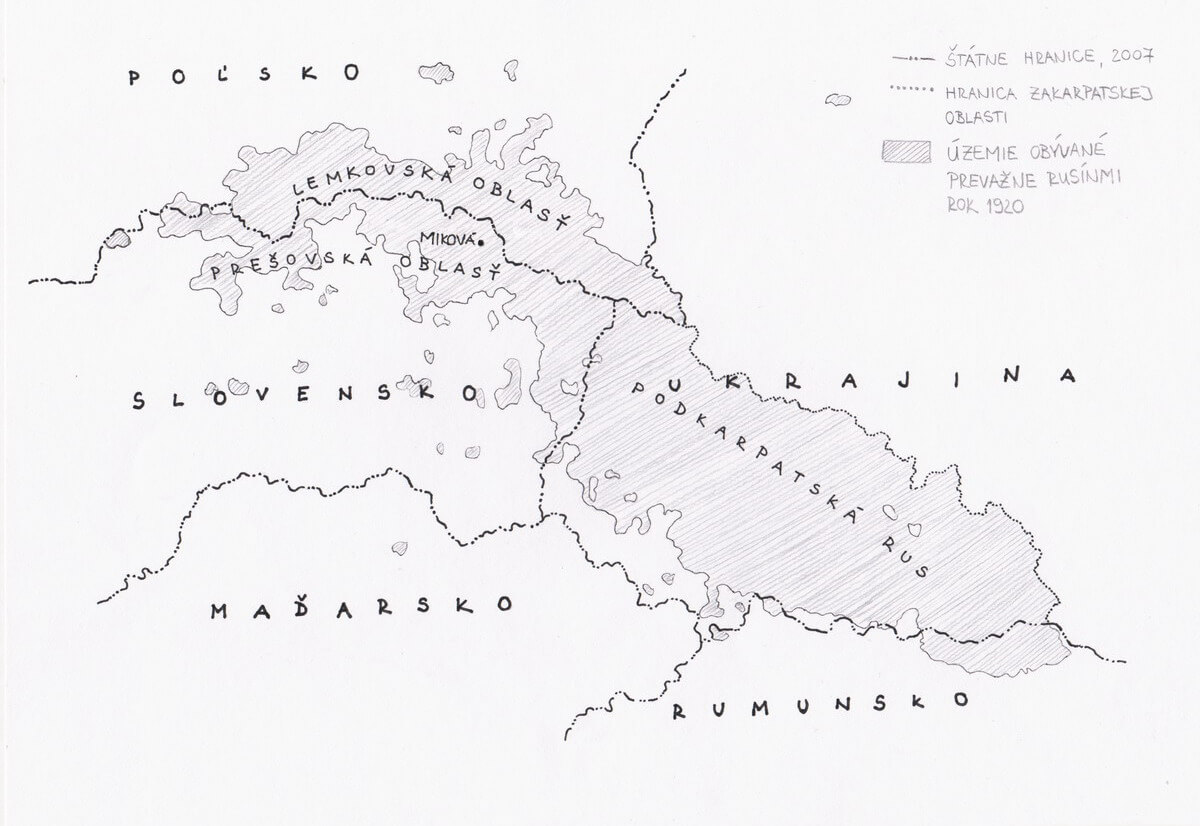

Andrij - Andrej Varchola was born exactly one hundred years before my birth, in 1886, in the valley of the Low Beskids, in a village called Miková. The picturesque village, situated on the outskirts of the monarchy, was made up of only a few inhabitants, and exclusively of an ethnic group called the Carpathian Ruthenians. At that time, the Carpathian Ruthenians inhabited the northern and southern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the Ruthenians formed the majority of the population of this territory. The area that Andrej would soon leave forever stretched over 365 kilometres in length. Carpathian Ruthenia lay in parts of what is now Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary and Romania. According to the current division of borders, Miková lies at the tip of the Carpathian Mountains in Slovakia, just a short distance from the borders of Ukraine and Poland.

At the end of the 19th century, living conditions in Miková changed as the population grew. The poorly fertile land around Miková could not provide sufficient sustenance for its inhabitants. Most of the villages in the area struggled with this problem.

On 17 November 1892 a beautiful baby girl named Uľa was born - in Slovak Júlia - Zavacká. And so, as her name foretold, one of the most romantic stories was waiting for her, set on two continents and places 7500 km away. When Júlia was born to her mother Justína, she already had a sister, Mária (Marja), two years older. After Júlia was born Juraj (Ďuri), Helena (Vlena) and finally Eva (Jeva), 15 years younger. It was Eva who, 50 years later, would receive power of attorney for all the inherited portions of the land, the little wooden houses, and the well that still survives today, belonging to Andrej and Júlia, who have been proud citizens of America for several years now. Júlia had fifteen siblings. When Uľa was a little girl, Miková had a population of less than 500 (it now has only 130 inhabitants). However, it was enough to divide it into upper and lower Miková. Each inhabitant, as was the custom not only among the Rusyns, lived for the land. Each family even had its own mill for grinding grain, which was absolutely unusual by the standards of other rural people from Slovakia. Both flax and hemp were grown in the village, which was used to make folk clothing. Families had livestock, and the family that had sheep made cheese, wool and processed sheepskin. Men in particular earned a living from seasonal work on the downs, but also in other, more fertile parts of the country. Over time, however, it became increasingly difficult to find work there.

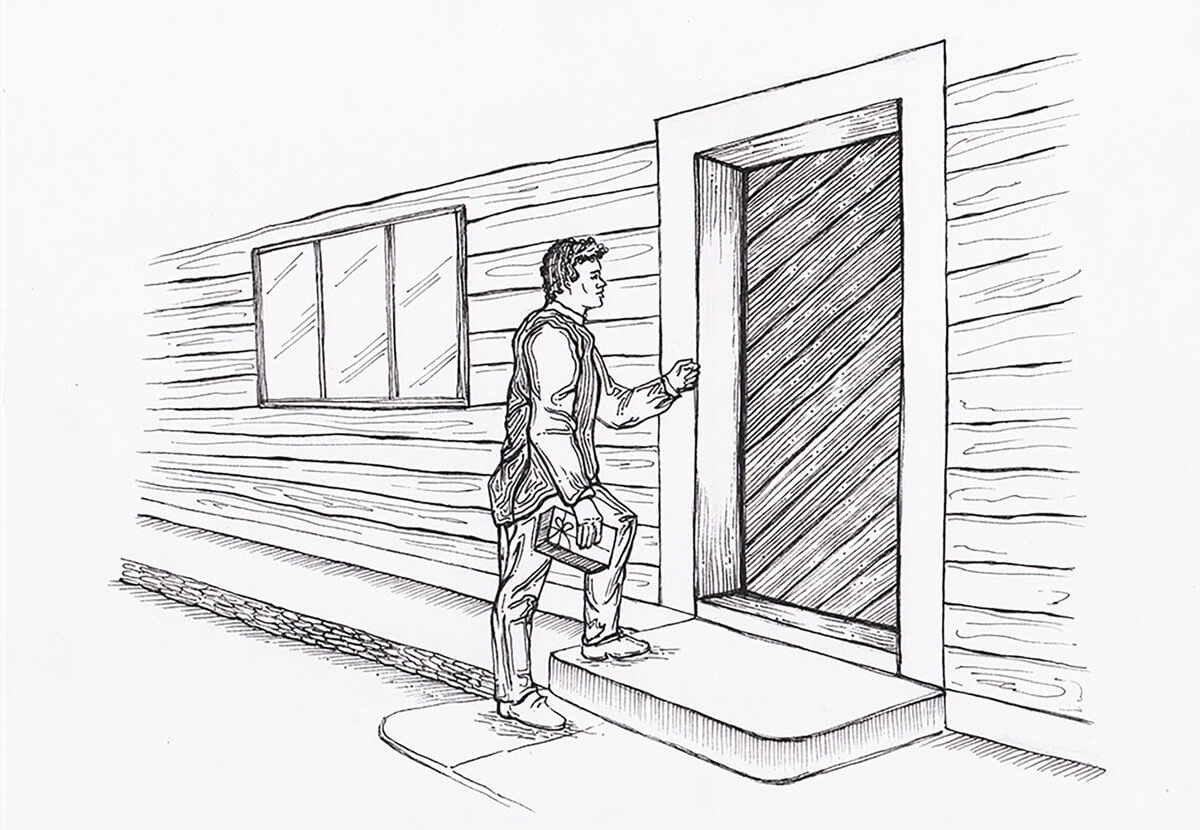

Both the Varchols and the Zavackys belonged to the wealthier families in Miková. However, the Varchols' fortune did not impress the young seventeen-year-old Júlia very much when the twenty-three-year-old Andrej showed interest in her. Both families came from upper Miková, and Júlia herself says that she made the final decision to marry only after Andrej brought her a sweet while courting her. What sweet it was that convinced the young beauty from Miková, we have no idea. But it must have been the best she had ever eaten. The truth may not have been hidden inside the tasty candy as much as it was Andrej's contacts and experience in America. Because both families were among the wealthier ones, it meant they could afford to travel to America.

"He looked good. Blond. My husband had curly hair. He was good-looking. Blond. My husband had curly hair. Oh! He came back to village and every girl want him. Fathers would give him lots of money, lots of land to marry daughter. He no want. He want me."

This is how Júlia Warhola described her love story in an interview with Esquire magazine. At that time, her already famous son Andy was very angry about the interview. "Why didn't they modify her English to something less peasant? She comes across as mentally retarded there."

Andy complained to his brother. Judging that his mother's immediacy didn't feed into Andy Warhol's long-built celebrity status and alter ego - Andy. "He came from America, I didn't know him. He walked past our house and he had a suitcase. “Hey Andrej, have you seen my sons in America?” My mom asked him. He walked in the house, oh how handsome he was, I'll never forget it. I came back from the field carrying wheat. I stayed on the grass and he looked at me. “Who is that little girl?” he asked. “She will be your wife!” My mother replied jokingly."

That's when love begins in the small village of Miková, which produced one of the greatest artists in our history. "I was 17, I didn't know anything. I didn't think about men. Everyone was forcing me to marry him. My mother and my father. “You'll like him”, they said, and a priest came and talked me into it. “This Andrej is a very good boy, marry him.” I cried."

Andrej does not give up and visits the Zavacky house again, this time with an effective strategy. "He brings me candy. I no have candy. He brings me candy, wonderful candy. And for this candy, I marry him.”

It was a beautiful day in May of 1909 when a significant event took place in Miková. A sturdy 165 cm tall and 83 kg weighing American man with blond curly hair marries a beautiful seventeen year old girl, Uľa Zavacká. The wedding lasted three days. Andrej wore a white coat and ribbons on his hat. The wedding menu was eggs, rice, chicken, pasta, bread and wedding cakes. Throughout the whole Miková, there were beautiful songs of the Roma band. “Wedding was beautiful, beautiful. Three-day wedding. I wear white. Very big veil. I beautiful. My husband had big white coat. Funny, funny. He had hat with lots of ribbons. Three rows of ribbons. A day and a half with my Mamma. A day and a half with his Mamma. Big, beautiful celebration. Eating, drinking, barrels of whiskey. Wonderful food—eggs, rice with buttered sugar, chickens, noodles, prunes with sugar, bread, nice bread, cookies made at home. Beautiful."

Seventy-six-year-old Júlia Warhola recalls, with a smile on her lips, to an editor writing an article for Esquire magazine about the mothers of famous contemporary celebrities (1966). "I had hair like gold, hair down to my shoulders, oh... beautiful hair, and what music, seven gypsies playing music. And now? It's all gone, I had big beautiful pictures of my wedding. Gone."

The first-born daughter of Júlia and Andrej Varchola was born three years after their marriage. It is not difficult to sense how desired little Josephine was. (Sources differ on the name - she could have been called Justína after Júlia's mother.) Her birth must have silenced any doubts about the young couple's fertility forever. After all, the main task of the marriage was to produce as many offspring as possible, helpers to a household in need of every capable hand. But man thinks... and neither superstition nor the protective magic of the shroud, which was supposed to protect mother and child during the six weeks of her childhood, protected the little six-week-old Jozefína from the cold that would prove fatal to her. By the time Jozefína flies like a little angel to heaven, Andrej is back in America. He only embarks on the journey to America after they finally manage to beget a child. Now it was up to him to provide adequately for his soon-to-be family of three in America. Júlia stays at her in-laws' house and, like any bride, performs the heaviest of domestic duties.“My husband leaves and then everything bad. My husband leaves and my little daughter dies. I have daughter, she dies after six weeks. She catch cold. No doctor. We need doctor, but no doctor in town. Oh, I cry. Oh, I go crazy when baby died. I open window and yell, ‘My baby dies.’” (She begins weeping.) “My baby dead. My little girl."

Júlia burst into tears in front of the editor of Esquire magazine, even though it's been 55 years since the event.

By the time Andrej leaves Miková for good, he's very likely running away from the draft order in particular. War is knocking at the door, and every deserting young fighting man is severely punished for his flight. We can only imagine how clever Andrej must have been in 1912 when he left for America without being caught. The draft order missed him by a whisker, so to speak. He escapes with his brother. The other brother remains in his native Miková. As it later turns out, this decision will prove fatal for the brother who stayed in the country. He dies at the front during the First World War or later from the effects of the war. Andrej escapes the gravedigger's shovel, but leaves his beloved wife at home, who will soon have the greatest tragedy a woman, a mother, can have. She lost her first born child. A new age, as it were, on the eve of war, brings new and severe penalties not only for desertion, but also for aiding and abetting desertion. But this did not deter the penitent agents, who quickly adapted to the new situation. No longer do they walk around in beautiful suits, top hats on their heads and hold gold watches in their hands to ogle. They change costumes like actors in a village theatre. They wear folk clothes and pretend to be villagers so that they won't be recognised. They know that they have one last chance to sell as many boarding passes as possible, because the coming war will surely stem the tide of emigration for some time.

“War, war, war. War start. Oh, you don’t know how bad. Soldiers come. We married in 1909. Andy leaves in 1912. He no want to go to Army, to war. He had $160. I stayed in Europe. He go to America. He runs in the night to Poland, only one mile away. He runs to Poland, then America. I stay in Europe.”

During the First World War, the Germans and Russians fought across the regions where Miková is located. Júlia, caring for her in-laws and younger siblings, experiences the cruelty of war firsthand. The area around Miková was littered with skulls and bodies of dead soldiers. Júlia remembers that it looked like large white mushrooms. They must have been hiding in the woods. Her house had been destroyed. It had burned down, everything was lost. She didn't have a father, he died a year after they were married, and her mother died the last year of the war in 1918. All the time Andrej tries to send Júlia money in an envelope, but it always gets lost along the way. They don't trust the banks. Before the war, money was sent by countrymen returning back home. But the war stopped this safest transaction flow for the villagers.

“My husband in America. I work like horse. His parents, old people, I live with them. I carried sack of potatoes on my back. I work and work. I was very strong lady.”

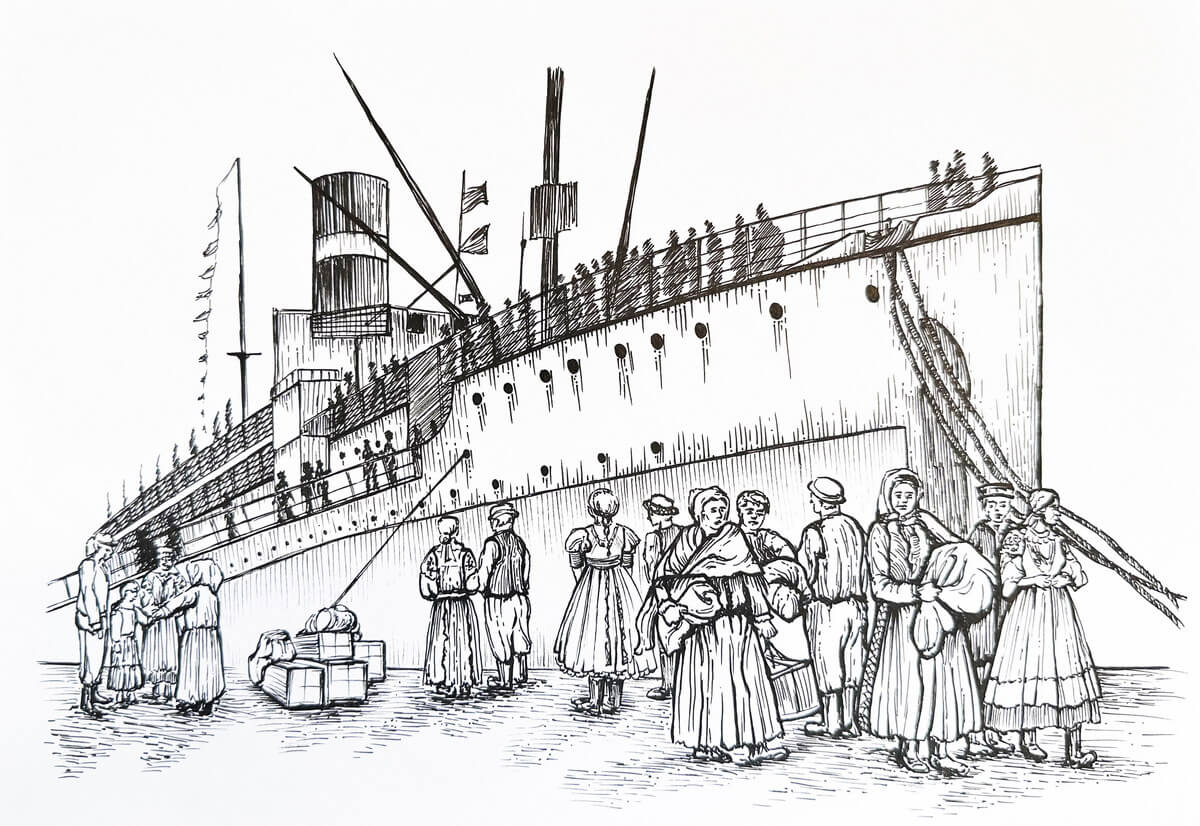

Andrej Varchola first went to America, according to various sources, in 1903/05/06/07/08. Whether he turned back that many times is questionable, but the history of migrants tells us that it is likely that he may have visited America several times. When he first traveled to America, he may have been something like 17 years old and employed as a miner in a Pennsylvania coal mine. As a Slav's first job in America, this was common. Decades before World War I, nearly a third of Miková's population had already moved to America. Emigration became the only way out of the near impasse of the difficult life of its inhabitants. From every house in Miková at least one family member left to earn money in America. In three decades, Slovakia lost about half a million inhabitants through emigration. Between 1890 and 1914, about 225,000 Carpatho-Rusyns emigrated across the sea and settled, just like Andrej, mostly in the industrial areas of America. They lived crammed on top of each other in rented rooms mostly with fellow countrymen. Other Americans found the way of life, many people crammed under one roof, incomprehensible, and there were various rumors about the not honest and debauched life of the Slavs.

Those from Miková were said to be very skilled and resourceful. They were able to construct their own wagons, tools for work, sledges, they could make almost everything by themselves. The men went to Lower Hungary for autumn and spring work, the women earned their living by steaming or weaving. Sheep breeding disappeared from Miková after the First World War. In addition to technical skills, there was talk of immense intelligence in the Varchol family and artistic and musical talent in the Zavacká family. Júlia herself was such a gifted singer in her youth that she "cantored" in church. This role was usually taken on by the ablest men in the village or the teacher of the folk church school and not by a young woman. When the church in Miková was being reconstructed in the early 20th century, Júlia was employed as a helper, patiently mixing paints and helping the master painters. Perhaps there, somewhere, a love of art was born in Júlia, which she later instilled with all her patience in all three of her sons, and especially in the most gifted and youngest, Andy.

In order to make the journey to America, many Mikovians sold their rolls to usurers and borrowed from relatives. At first, no one even thought of staying in America permanently. They took America just as they took seasonal work in the southern areas. They learned quickly in America, worked hard, and as soon as they saved the necessary amount of money, they immediately returned home to their family. With the money they earned, they bought a piece of field or built a new log cabin. They also brought new knowledge and innovations from America. In addition to the hard peasant life, the Hungarianization of Mikova began to grow stronger, which may be why many Ruthenians from other villages also chose the direction of a free environment in America. The goal was Hungarianization of the non-Hungarian population in the Kingdom of Hungary through a set of various measures, practices, and efforts of the government and other institutions. The activities of Ruthenian associations were restricted and the teaching of the Ruthenian language was stopped. Life in the classical Ruthenian family in Miková was strictly rationed. Each member of the family had important responsibilities. The five-year-old children herded the chickens, geese and later took care of the pigs. Eight-year-olds took care of the cows, which had to be herded out to pasture, sometimes for days and nights at a time. It is likely that the choice of which son would go to America was made by the parents themselves. The first emigrants from our territory were mostly illiterate, that is, they could not read about America, the promised land, from pamphlets or newspapers. Letters from other emigrants played an important role, giving florid descriptions of life beyond the Great Puddle. These letters were read to the villagers by a teacher or parish priest. Occasionally, half the village would come together to read the letters. It was almost a daily occurrence to meet agents in small villages who were luring young men to come to America. They told stories of the rich continent where gold lay on the ground. All one had to do was bend down and pick it up. Apparently they travel to America by boat bigger than their village. And thanks to the good heart of the agent, who is only too happy to take an immediate deposit for a ticket aboard such a steamer, they have a place booked immediately. As soon as the gendarmes arrive in the village, the agents go silent and pretend as if nothing has happened. Making propaganda to the emigration was punishable. Although it was not forbidden to emigrate from Austria-Hungary, it was strictly forbidden to hire emigrants or sell them tickets. The harshest punishments were for those who recruited men of fighting age. It was considered aiding and abetting desertion. In the late 19th century, guys were paid $1 for a shift in America, such as in a coal mine. A ticket in the cheapest class on a steamboat to America cost $34.

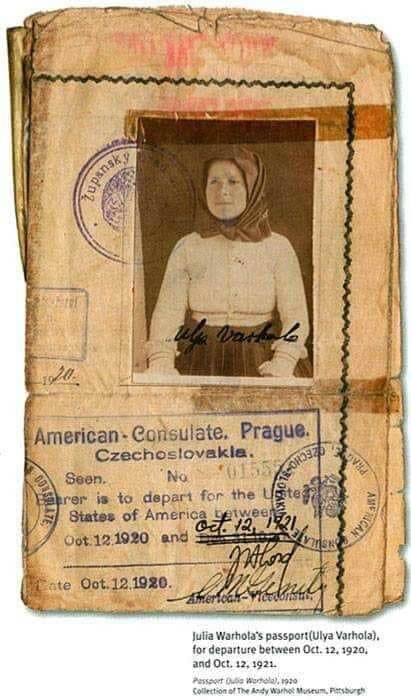

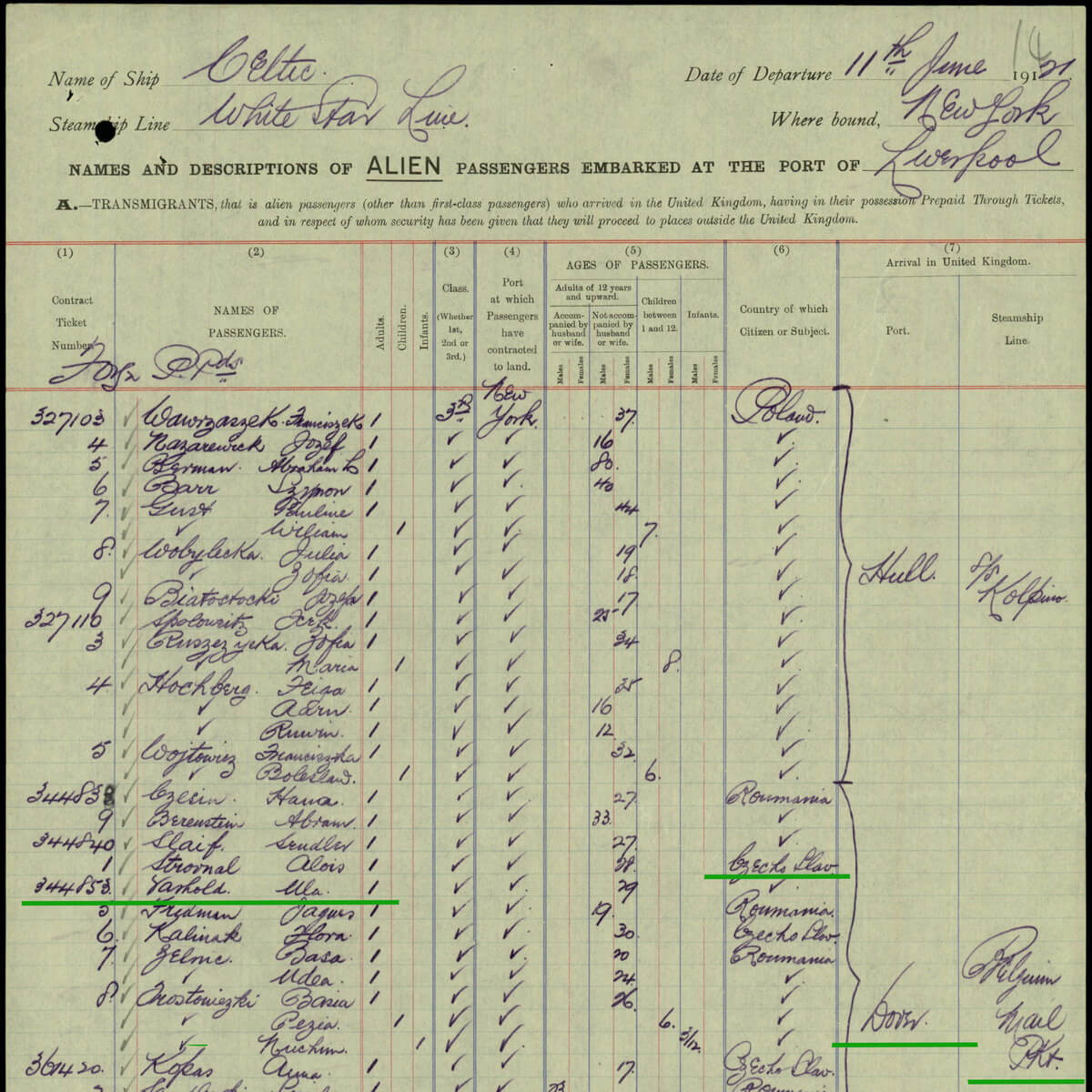

Autumn is already beginning to fall when on October 12, 1920, a severely tried 28-year-old Júlia Varchola sits in her festive Miková folk costume, wearing a blouse with delicate cross-stitch embroidery, a folk bonnet and a scarf of a married woman at the American Consulate in Prague. Its branch is in the capital of a new state called Czechoslovakia. The new borders have assigned a small Ruthenian village called Miková, of which almost nothing remains, under Czechoslovakia. During the war, the efforts of Rusyn emigrants in America were noted - they founded the American National Council of Uhro-Rusyns. 67% of the members of this council agreed to the annexation of Subcarpathian Rus to Czechoslovakia. We can only guess whether one of the voting members was Andrej Varchola, who had not seen his beloved wife for 8 years. It was in the tense post-war period, when even Júlia herself may not have known what nationality the ship's guide would write on her passenger list when she left for America, that Júlia began to hope. Hoping that she would be able to meet her husband after many years of bloodshed. On October 12, 1920, Júlia left Prague for home, holding her passport with her photo, or rather, her visa to America, valid for exactly one year. She has a year to buy a boat ticket and leave. But this seemingly small thing, which for us now takes only a few clicks, is about to get really complicated.

Who knows if it was divine intervention that will forever affect the story of Júlia or just a reward for the fact that despite the harsh adversity, Júlia never lost her faith. It's been months since Júliia made her visa to America, and time is beginning to press inexorably upon her. She may go to the post office every day, which is in the next village, Havaj, 6 km from Miková. She is waiting for a letter from Andrej with instructions and money for the trip. He tries to send her money several times. Unfortunately, the money always gets lost on the way. In the spring, when the cold winter passes, Júlia begins to act. She cannot wait any longer. Maybe she doesn't want to travel in the winter because the journey she takes is hard even in the summer, much more so in the winter. Andrej sends her a letter with the last instructions. It probably said in which Polish city, in which office that sells boat tickets, her boarding pass from the White Star Line awaits her for the steamship Celtic bound for America. That city could have been Katowice or Auschwitz, for example. Both were offices of shipping companies. How she would get to Katowice was now in Júlia's hands alone. She borrowed money for the journey from the parish priest of Miková and had to promise to name her first-born son after him - Konštantín (her husband, Andrej, apparently did not agree to this arrangement, because the first-born was named Paul).

This scene is like something out of a romantic movie, when a young woman runs towards love and everyone around her wishes, helps and blesses her.

At the beginning of June 1921, she packs only the bare essentials and bids a final farewell to her native village, boarding a carriage that will take her to the train station less than 15 km away - to Medzilaborce. As soon as Júlia arrives in America, she pays off her debt and sends the borrowed money to the parish priest in Miková.

It is very highly probable that Júlia got off the train somewhere in these places. Over 100 years ago, this place was crawling with people. People mingled in the station with agents selling "chiclets", trying to literally grab the confused passengers, many of whom had already purchased their boarding passes, under their arms as quickly as possible. Under duress, they were taken to the agencies, where they were often forced to buy tickets, repeatedly claiming that the first one (perhaps from a competitor) was invalid. These cases happened especially during the time when Júlia's husband Andrej was traveling. Since then, new laws have been introduced, even huge lawsuits have been recorded where many witnesses have testified against the agencies and agents. I want to believe that when Júlia stood on this spot in June 1921, such coercive practices were no longer happening. She may have been waiting at these locations for an agent to show her the way to a nearby agency where she picked up her cipher card, as one of two women from Miková, that her husband Andrej had purchased in America. The other woman from Miková also boarded a train at this station, but in the opposite direction. Towards home. Júlia still has a long journey ahead of her here, as I have tomorrow towards the port of Gdansk.

According to old railway maps, we deduce what the journey of Júlia and another woman from Miková, Mrs. Prekstová, who traveled with her, might have looked like. After all, when two are going, it's a bit safer than when a woman is sailing alone. It is possible that we may be mistaken as to the exact route they took. This information is not publicly available and it is possible that the family members don't know any more than we do. The closest train crossing over the Czechoslovakian border into Poland was via the Lupkovsky Tunnel. We assume that at Medzilaborce, Júlia would board the train, pass through the Lupkovsky Tunnel via Lupkow and probably change trains at Zagórz, perhaps further on, in the direction of Krakow and then Katowice or Auschwitz. There is an office where she is to collect her boarding pass for the steamboat to America, which has been purchased by her husband. With today's train connections, the journey from Miková - Medzilaborce - Lupkow - Katowice takes approximately 10 hours. We can only imagine how long the journey must have taken over 100 years ago. Two courageous women from Miková arrive full of enthusiasm at the office in Poland, but instead of enthusiasm they are met with a very bitter disappointment. One of them does not have a ticket. She has to return and make the ignominious journey back to Miková. Júlia, however, had a ticket, only she is left to make the arduous journey alone. Without knowing the language, she has to go through harsh checks and inhumane conditions to meet her beloved husband, whom she has not seen for 9 years, across the sea, where she will see the Statue of Liberty.

With visa in hand, boarding pass and some money, twenty-nine year old Júlia Varchola (Uľa Varhola, Júlia Warhola ) boards a train alone, bound for the free city of Danzig (Gdańsk). A year before Júlia's arrival, the citizens of this city are granted independent citizenship, with which they have lost their former German citizenship. Danzig is a huge strategic and prosperous port located on the shores of the Baltic Sea. It was here that the regular Red Star Line apparently "sailed" carrying many passengers from our and Polish territory. We must not forget that the war ended recently and perhaps because of the devastated railways in German territory, it is the northern route that Júlia is taking. In the Polish port town they are used to our people. Júlia, her clothes, her speech and even her appearance is nothing unusual. Even the fact that she is a woman traveling alone is not unusual in 1921. It was in this later wave that many more women began to travel to America, and even with very young children. The wave of emigration in the year of Júlia's journey is at its peak. And the more people traveling, the more invisible and even visible enemies she as a woman might encounter along the way…

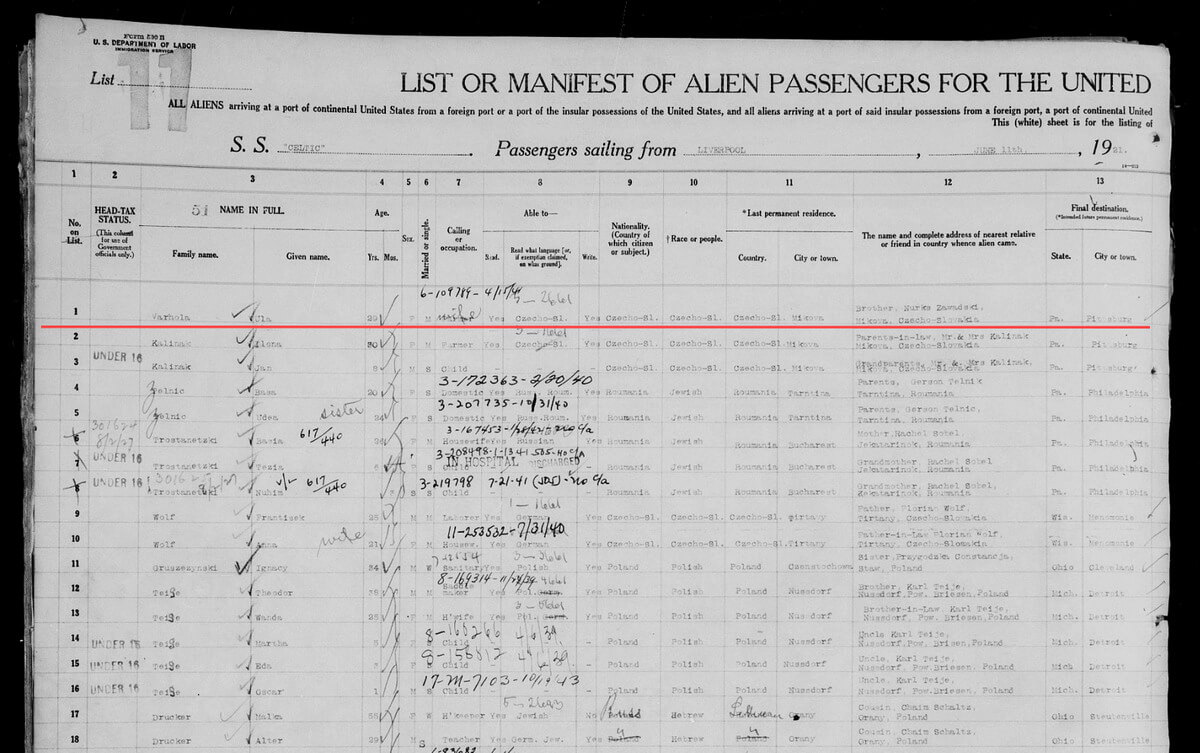

We assume that in Gdansk, Júlia boarded the first big ship she had ever seen in her life. But it wasn't the biggest one yet that would take her across the ocean to her husband. Red Star Line is a Belgian company and operates a regular service between Gdansk and Antwerp or Ostend. In one of these Belgian cities, Júlia disembarks to board another shuttle, this time on the mail steamboat "Belgium Mail". She leaves the old continent and for the first time in her life disembarks on English-speaking soil, in Dover, England. From England, thanks to digitisation, we have for the first time handwritten evidence of where Júlia traveled. How long her previous transfers may have taken we don't know, but on the current Gdansk to Antwerp train service it's about 17 hours, and if we add in the transport from Belgium to England, this journey could have taken her a whole day. We see much more in the entry with the ship's officer at the later English port of Liverpool. We see the date 11 June 1921 and we see that Júlia arrived by Belgian ship. We also see the happy news that there are quite a number of Czechoslovaks traveling with her on board the Celtic. This gives us hope that Uľa's journey, which apparently lasted 9 days, was made more pleasant by the company of her compatriots. The Statue of Liberty is the first thing the new residents of America see. It welcomes them with open arms and gives hope of a better life. Júlia entered the American continent on June 20, 1921, and never physically returned to her home, although she did not break contact with Miková for the rest of her life.

"Passenger screening started in the early hours of the morning. Officials from the transport company checked our passports and boarding passes while a doctor examined everyone's eyesight, hearing and skin. When we arrived at the port, the sun was already high. There we saw the Lahn, a steam-powered iron ship that could hold more than a thousand passengers, most of whom were emigrants like us traveling third class. The youngest children began to cry with fright as soon as they reached the gangway. Antek had to be urged on with a nudge from his father before he stepped onto the rickety corridor. The women prayed silently and walked forward as if blindfolded. In the hold were large rooms filled with bunk beds. We were very lucky, for there were not enough beds for everyone. Several families had to spend the entire trip on the metal floor. My mother was embarrassed by the male stares and worried about her belongings and her children, especially me, as I was being harassed by some strangers. When the sirens went off, the boat shuddered and slowly headed out to sea. There was no turning back."

This is how the memoirist - an emigrant from Poland - describes her experience of traveling by boat. I found this quote in the emigration museum in Poland.

I am currently standing in the English port of Dover. Júlia (Uľa) disembarked here for the second time, but the most demanding voyage on an ocean liner is still waiting for her. For the first time, she travels by ship Gdańsk - Belgian Antwerp/Ostend. There she transfers to a Belgian mail ship in the direction of Dover. In Dover, where I am standing right now listening to the sounds of the sea, she gets on the train to Liverpool, 480 km away. According to our estimates, she has just completed more than 10 days of travel and has at least the same amount to reach her destination, Pittsburgh, USA.

Most of the emigrants traveled to America third class. This name was given to the parts located below deck and often below sea level. It was characterised by overcrowding, filth and stuffiness. In the recollections of poor emigrants, the "passage" often appears as a dramatic experience: "Great confusion on board. When the ship left port, there appeared to be more passengers on board than beds. It couldn't be helped and so the group of passengers were left without beds for the rest of the voyage. I was one of this group. Where did I sleep? Where I could. Mostly with a friend from a neighbouring village. Although his bed was only two feet wide, we both fit as we lay sideways. There were no cabins, just huge rooms with iron beds, three bunk beds on top of each other. Several hundred people could fit in each room of this kind. When the sea was calm and the people were healthy, it wasn't so bad. But when the ship started rocking and people got seasick and started throwing up from the bottom, middle, and top beds, then the whole room turned into one huge puddle from which the stench rose in clouds of vapour."

A passenger from Poland describes his experience. Between 1815 and 1930, 60 million people left Europe, 32 million of them to the USA.

More than 600,000 people emigrated from Slovakia in this wave. Try to imagine the ratio to the population at that time how many people that was. Two of these people were our main heroes, Andrej and Júlia Warhola. The reasons why they did so do not need to be explained to anyone. Had it not been for their brave decision, there would not have been one of the world's most famous artists, Andy Warhol.

The administrative processes at Ellis Island were often cruel and inhumane. Every day, new and new boats brought in thousands of immigrants, most of whom did not understand a word of English. The process was lengthy and humiliating. At the slightest sign of illness or sickness, the doors to America were closed and the tired, exhausted and worn out immigrants were sent back to Europe at the expense of the shipping company. Hundreds of people crowded into the cramped hold, a breeding ground for a variety of diseases. Tensions must have been running high at Ellis Island. The fate of each person was decided by a single official who only let the healthy and strong go. From contemporary documents we learn an unexpected piece of news - "Uľa Varhola" arrives on the same ship as "Kalinak Ilona" from Miková and "Kalinak Jan" from Miková (he has a marking of less than 16, so he was a child). We quickly went back to the Livepool list in our search, and two names below Júlia's we found the name Kaliňak Ilona again. From all the available records of Júlia's travels, we knew that she had made the journey alone, at least in Europe. There was only one "cipher card" waiting in the office that sold tickets for the steamer bound for America for the two women from Miková who were going out into the world. The other had to go back. But thanks to the meticulous American administration, which has only in these years gone digital, we apparently learn that Júlia, at least, was not entirely alone on the ship. Whether the old familiar rule "Slovakia is a small village" worked, the two Miková women and one small son met by chance in the port of Liverpool or whether they traveled together from the beginning, we will never know.

It's hard to imagine the culture shock of contrasting a small village of 500 people on the edge of the Carpathian Mountains with a city of tall skyscrapers like New York. But our protagonist didn't stay in New York for long. After the harrowing bureaucracy of Ellis Island, she can finally step onto American soil in peace. Whether her dear husband was waiting for her at the port, we do not know. But we assume that she is traveling alone to a city of 600,000 people, probably accompanied by her compatriots, and her husband is again on shift. It must have been a strange sight to see the inside of a train that traveled over 8 hours to industrial Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 600 miles away. A train in which all Czechoslovaks were crowded close together. Perhaps because of their presence on the train, they did not even realise that they were over 5,000 km away from their own homeland. The view from the train window must have been beautiful. Forests resembling the forests around Miková, mountains almost identical to the ones lining the border to Poland, and beautiful clear blue lakes. However, no idyll lasts forever. The train arrives in the capital of Pennsylvania, and when Júlia steps off the train, she is engulfed in a cloud of acrid smog. Andy Warhol called his hometown: "The worst place in the world, when you went out in a white T-shirt, turned dark grey." During his 36 years as an artist in New York, Andy never once visited his hometown. This grey industrial city called Pittsburgh would become Júlia's home for several decades.

When Júlia Warhola arrives in Pittsburgh, she sees her husband after nine years. In those nine years, as many events have happened to her as don't happen to someone in ten lifetimes. She has buried her parents, in-laws, other relatives, and most importantly, she has lost her first-born daughter. She survived the war, the evacuation of an entire village and total poverty. She also survived the burning of her home, all without the support and presence of her beloved husband. Who knows if they even knew each other at first sight. Who knows what their first encounter was like. Whether they ran to each other and all the weight that Júlia had carried on her shoulders up to this point finally lifted. She is in the arms of a man who will take care of her. She is no longer alone. At 29, Júlia's age, and 35, Andrej's age, these two lovers are getting a second chance at a life together.

Andy's father, Andrej, became a proud official American a few months before Andy was born. Andrija Varchola became Andrew Warhola. He worked at the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. The town they lived in mixed myriad ethnicities and nationalities. Italians, Germans, Irish and Jewish immigrants all lived in one place. At first, Andrej was unable to secure housing in a neighbourhood where they spoke "our way," called "Rusyn valley." Where did the inhabitants of "Rusyn valley" actually come from? Were they Serbs? Croats? Romanians? Certainly not. Their language resembled Slovak, a little Russian and Ukrainian. They were Slavs, calling themselves Ruthenians or Rusyns or Rusnaks. The “Zavackí” family (Júlia's family) living in America sometimes referred to their nationality as Russians. Because people knew Russia because it was a big country, even though they knew that wasn't true. A neighbour living next door to the Warhols described them as Slovaks or Poles. Americans derogatorily called them "Hunkies." Their first apartment was on Orr Street. It had two rooms and was on the second floor of a wooden row house. The water was only cold and the toilet was outside. It was in such an apartment that Júlia brought Paul, John and Andy into the world. The last Andy, who would become one of the world's most famous artists, was born when she was 36.

Within two years of Andy Warhol's birth, the Warhols moved twice on the same street. The three boys slept together in the same bed. As brother John said, they never felt they were poor. Because everyone around them lived exactly the same. They lived with another family in the house they moved into and paid $18 a month, which was about a quarter of the family's monthly income. Andy Warhol bravely avoided the subject of his roots when interviewed. When he came to apply for a job at a magazine in 1949, he was asked by an editor for his biography. "My life doesn't fill the size of a small postcard". He also lied frequently about the date of his birth. Once he was born in 1929, then in 1930, and sometimes in 1933. He also lied to his own doctor about his date of birth. "I never reveal my background, no way, whenever someone asks me about it, I change my version." Júlia cooked with the help of coarse cookware, which her husband Andrej, like a properly skilled Mikovian, had made himself. They cooked the soup with water, leftover ketchup and spices. When they could afford a house and a garden, she grew tomatoes and root vegetables. They raised their own chickens in the garden and had homemade eggs. The family also made their own "kolbasi," rather than having to buy them from the butcher. Even when Andy's career was in full swing, Júlia preferred Sunday's homemade chicken broth to simply buying it and opening it from a Campbell's can.

A few days after Andy's sixth birthday, just as he started primary school, his family moved to Dawson Street. Andrej's brother, Jozef, lived next door to them. Both brothers had the same scars on their faces. They'd had them ever since they'd fought at the wedding. People were afraid of both brothers. The house was charred on the outside and was only 8 years old. It had a garden and a bathroom. In today's terms, its price was worth three years of a man's labor. Andrej had a reputation for being a thrifty man. He repaired his three sons' shoes himself, and the tools he used to repair them still exist today. He took advantage of a period of economic crisis and scarcity to renovate his house. Neighbours described the Warhols as ambitious and hard-working Slavs. Júlia helped the family budget by cleaning houses of wealthier Jewish families and selling various products door-to-door. Since they had no money to spare, toys were not bought in the Warhol house. They didn't even have a radio in the house until Andy was eight years old. Júlia, however, kept the boys occupied with art. She always rewarded good pictures with candy and made sure art supplies were always available in the house. They looked for their inspiration in magazines or football cards. Andy liked to draw flowers, butterflies and angels. It was the angels that young Andy could identify from the many drawings of his equally talented mother. When critics wanted to write a book about Warhol, the artist countered, "That book should be about my mother, she's so interesting."

When the Warhols were buying a house, it was very important how far it was from their family temple. Historian Martin Javor, who, in addition to founding the beautiful Kasigarda Museum (Kasigarda is the imitation of Slovak pronunciation of England's Castle Garden, the main gate of the New York City immigration office through which every immigrant had to pass in the days before the Ellis Island reception buildings were built), mapped all the temples built by Slovaks in America. There are 720 of them in total in North America, of different denominations - you can see them in detail on the interactive map at www.kasigarda.sk .

The Warhol family temple, Saint John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church, in front of which I am standing right now, was built by Slovaks. It is located down the hill in the "Russian Valley" and the family visited it every Sunday. It was even forbidden to work and even play on Sundays. In this the father - the head of the family - was strict. The future famous artist was also baptised in this church.

Andy was sickly from a young age. Perhaps when Júlia saw how sick he was getting, she was afraid that history would repeat itself and she would lose another longed-for child. Therefore, Andy had special privileges in their family and had to spend a good part of his childhood in bed, in the care of his mother. Today we know that Andy suffered from a disorder called PANDAS. It is an autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection. One of the symptoms of PANDAS is extreme clinging to one parent. Andy used to sleep in bed with his mom in the dining room and the other brothers slept with their dad upstairs. "My mother would read books to me in English with a strong Czechoslovak accent as best she could, and whenever she finished I would say 'thank you mom' even though I didn't understand a word."

Being sick gave Andy a chance to live a life filled with culture. Júlia always told him he couldn't go everywhere and couldn't do everything. This meant that summers, unlike the other kids playing outside, Andy spent them in his room in bed with the radio on.

"Andy always wanted pictures. Comic books I buy him. Cut, cut, cut nice. Cut out pictures. Oh, he liked pictures from comic books." Júlia recalls in the middle of an Esquire magazine interview.

"Andy, he look like me. Funny nose. …Andy was nine years old. Boy, now big man, come here and say someone wanted to give him $300 for picture. (She laughs.) Oh, Andy a good boy. He’s smart. His schoolteacher, a lady, tells me he teaches himself good."

Júlia even pawns her earrings without her husband's knowledge and buys her youngest son a projector for $9.

In times of recession and economic crisis, Júlia is trying to make as much money as she can. Apart from cleaning and door-to-door sales, she is looking for other creative ways to make a living. She cuts bright flowers out of peach tins and sells them for a few cents to save money for her son's new shoes. Andy would later admit that these flowers were his main inspiration for one of his most famous works, "Campbell's soup". When their father Andrej finally finds a new job with a company moving houses across America, tragedy strikes after a long time. Family legend has it that Andrej drinks from a poisoned river in Virginia and, as a result, dies a long and painful death from poisoning. In 1942, when young Andy was 13 years old, his 56-year-old father died after a 9-day hospitalisation in the hospital. However, the official autopsy report disproves the family legend. Cause of death: tuberculosis. According to the customs of the Carpathian Ruthenians, the body remains exposed at home for 3 days. Andy was so afraid of seeing his dead father that he avoided the place where he was exposed. Júlia is left to care for her three sons alone. Fortunately, Paul is now an adult, 20 years old, John is 17, and Andy will soon have a fresh start in high school.

A few months after his father's death, despite his mother's unenthusiastic consent, the eldest son marries a girl whose roots go back near Miková. The expectant couple move into the top floor of the house and pay rent to Júlia. To make ends meet, the family rents out one of the rooms to returning soldiers for $5 a month, working steadily as a housekeeper until she is diagnosed with a serious illness. 51-year-old Júlia suffers from colon cancer. "I'll never forget the day Andy walked into the hospital and asked ,did mumma die?" recalls Andy's older brother. "He was very sad about it, so we listened to mum, prayed, prayed and prayed." Mummy was visited every day, and perhaps somewhere in there Andy's almost panicky fear of hospitals would arise. The surgery saved Júlia's life, but the care of running the household and the younger sibling had to be replaced by the older brothers. Perhaps that's when the Warhol household is first visited by a can of soup that the brothers eat almost every day.

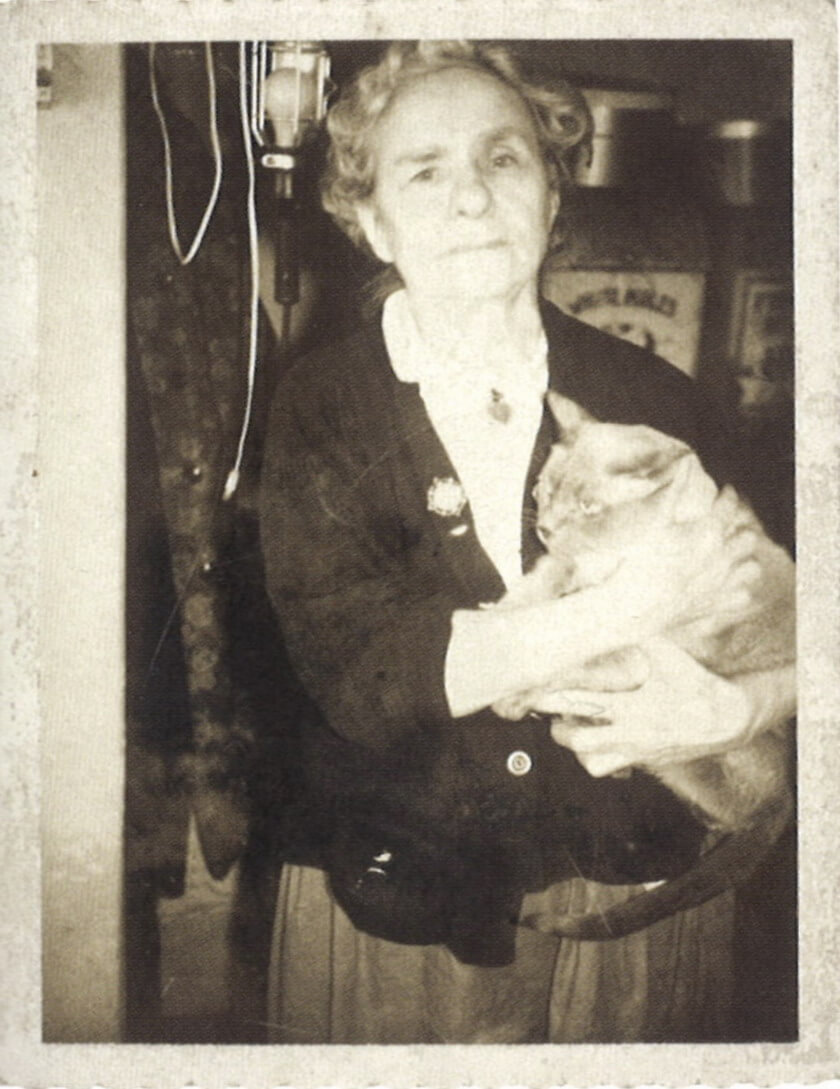

Perhaps marked by her husband's death and serious health problems, Júlia Warhola, a proud, official citizen of the United States of America for several years, decides to clean up the family holdings in her native land. Like her, her three sons also renounce their inheritance of land and real estate in favour of Júlia's younger sister, Eva. It is with Eva that she is in constant correspondence. Apart from parcels, postcards, letters with drawings and photographs, in which she proudly poses with her appearance immaculately neat. A necklace of white pearls shows that the photo is of a true American lady. But, like all of us, she spares no self-criticism. "Andy has this machine at home that takes portraits in under a minute. Don't show it to anyone because I look really bad in there. I'm not as old as I look in that picture." "This is me with my cat, we're both old now. That's how bad Andy took that picture of us, you're going to laugh my dear sister. Very badly." In one of the packages for Eva, there is something that was a straight breakthrough for those of us who have been retracing Júlia Warhola's steps. For the first time, thanks to creativity and artistic talent, we can hear a voice as soft as bells, belonging to a 50-something year old Júlia Warhola.

As a gift for her sister, Júlia recorded Ruthenian folk songs in an American recording studio, not forgetting to add her own spoken commentary to each song. Decades later, thanks to the favourable paths of fate in Slovakia, the record has been digitised and so we will hear Júlia Warhola's voice in our upcoming documentary.

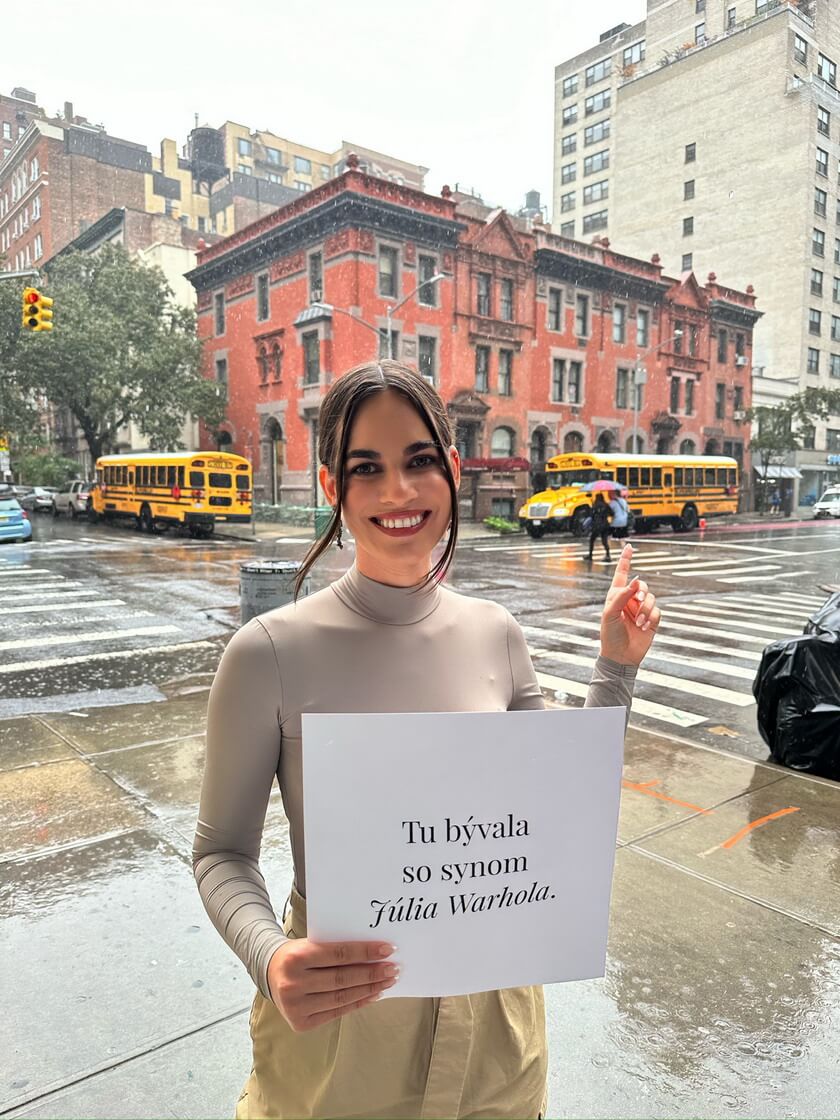

On a winter day in 1952, Júlia comes to visit her, by then famous and extremely busy, youngest son in his New York home. To the surprise of all her relatives, she does not return to Pittsburgh for nearly two decades. "I've come to take care of my son Andy, and when he's OK, I'll come home." A trusted friend of Andy's commented tellingly, "Andy is never OK," and a caring mother who knows her son knew this all too well. He was in dire need of someone to look after him. When Júlia arrived, she mentioned that she had found 97 unwashed T-shirts in her son's closet. We don't know why they had been separated for almost 3 years, but on that winter evening, the mother again became a fixture in her son's daily life. Joseph Giordano, who visited Andy's house, described Warhol's mother this way, "More amazing than possible, much smarter than Andy." "Once, after an argument, she haughtily left for Pittsburgh, only to return immediately, demanding respect. She came in, slammed her suitcase on the ground and turned around screaming, “I AM ANDY WARHOL!"'. Giordano was the only one who saw her as the source of the artist's problems, but also as the source of his inspiration. All of Warhol's acquaintances were taken aback by her presence in the house. She cooked and cleaned like a "Czechoslovakian housewife" and cooked for her son and for anyone who visited the house. The son and mother spoke "our way" to each other, but switched to English the moment guests visited the house. In Júlia's case, very broken English. At home they ate "Czechoslovakian food", although in the media Andy always presented himself as a proud American, fond of white bread and milkshakes. For dinner, Júlia used to cook cabbage dishes and the very popular "Czechoslovak stuffed pancakes" for the guests. Whether these were our pancakes or our potato pancakes, we don't know.

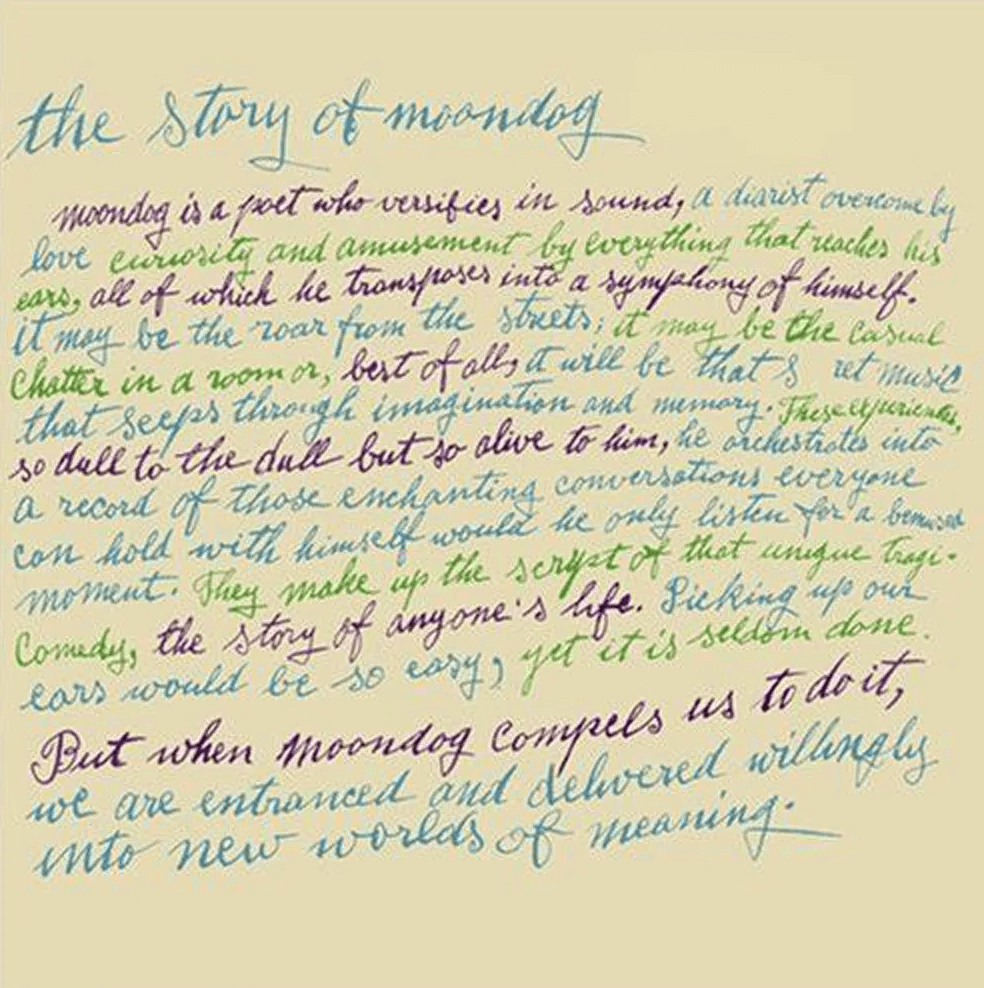

Júlia was, according to witnesses, "as funny as Andy, she loved to laugh at ridiculous things". Andy Warhol's assistant compared Júlia to the artist Grandma Moses. Her son also revered his mother for her artistic work. "Very good and proper, not primitive." Her absolutely iconic calligraphy, with which she made descriptions for Andy's works, was not her own. Indeed, Warhol's father and other native Rusyns had also taught her to write with a steel pen dipped in ink. Her writing, aside from the many errors, was a perfect complement to Warhol's style. Júlia's handwriting plays another important role. Andy read a passage in the book where it says that interesting cursive is a sign of personal "otherness." In 1957, 65-year-old Julie wrote in her cursive handwriting on all of Andy's important commissions. Júlia also created her own alter ego, which she called MOONDOG; it was her cultural double. The short story about Moondog, written in Júlia's typical calligraphy, depicts a blind outsider and a homeless man. Júlia's unique handwriting in Moondog even won an art printmaking award. However, the winner was not Júlia herself, but "Andy Warhol's Mother." In fact, many people thought that Andy's alter ego, and not Andy's real mother, had entered the contest. Júlia did not have the strength to continue her artistic expression. Over time, Andy and his assistant both learned Júlia's calligraphy and continued it without the need for his mother's presence. As time progressed, Júlia became more and more withdrawn and retired into the background. "Mrs. Warhola was not glamorous and I think he was kind of ashamed of her. But if you met Andy's mom, you'd know he liked her a lot," said a friend of Andy's.

"My son works a lot, is at home a little and travels a lot by plane", Júlia complains in a letter to her family. Even the presence of many cats, most of them named Sam, does not fill the emptiness in her house. Perhaps it is during this time of complete solitude that Andy's most famous drawings, "Holy Cats by Andy Warhol's Mother", are created. She certainly made friends, let's call it more like she had social contacts, at least at the church she attended every Sunday. The temple was frequented mainly by Ruthenians and was 75 blocks from their New York home. She contributed $100 a month to the church and sent money to the family in Miková as well. "I'm not that close to my mother, a lot of people like her better and get along with her better, they prefer to talk to her," Andy confesses to a friend. On June 3, 1968, nearly 50 years after the young woman set foot on the soil of the Promised Land, another tragedy happened to the devout and well-liked woman. Her son is shot by an insane former actress from Andy's films. A son with whom she has shared a household for 16 years. Andy narrowly escapes death.

In Andy's personal diaries, which he recorded to his assistant over the phone, he mentions his mother only very briefly. If at all. "You know, I still get stuff from the Czechoslovakian church because they probably don't know that Mom went to heaven. And I always think about Mom at Christmas, if I did the right thing sending her back to Pittsburgh, I still feel guilty." Toward the end of Júlia's life, a rare recording is made. "Who will be with me when you go to Europe? Will you lock the house? They'll steal everything from your house, they'll come at night, my son," Júlia says in Ruthenian, already slightly disoriented, to the new camera her son is testing. He answers her in English and asks if he should make her potatoes or a sandwich. Júlia is suffering from incipient dementia, and her presence saps the energy of the not-so-long-ago shot, perpetually ill, at the time very famous artist. The brothers decide to place their mother in a retirement home where they will be able to care for her much better. The bills for the new home are paid in full by her youngest son Andy. "I don't think your mother will be in this world much longer. I look forward to the news when you honor your mother with her last wish in the world, to see her son one last time. You!" his cousin writes in a letter to Andy after a visit to the nursing home. On November 28, 1972, just after her 80th birthday, Júlia Warhola died. Andy can't attend the funeral, it makes him too nervous. He reminds his brothers to try their best to keep his mother's death a secret from the public. Júlia Warhola is buried with her beloved husband in the same grave in the Pittsburgh cemetery. A few dozen inches away, just in sight of her caring mother, we also find the grave of one of the world's most famous artists, Andy Warhol.